Higher Education Anti-Racist Teaching Podcast

The Higher Education Anti-Racist Teaching (H.E.A.R.T.) Podcast focuses on elevating our learning about anti-racist teaching at colleges and universities.

In this series of podcasts, we explore what antiracist teaching in higher education is, what it entails, what challenges educators face, and any advice our guests can give our audience in their antiracist teaching journey.

The podcasts are co-hosted by Dr. Milagros Castillo-Montoya and doctoral student Omar Romandia. With a strong commitment to centering the learning of BIPOC students, they ask questions of their guests to deepen conceptions about antiracist teaching as well as advance teaching practices that align with antiracist tenets.

The podcast is supported by the Office for Diversity and Inclusion and the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at the University of Connecticut.

SEASON 3

Planation Politics and Campus Rebellions (Feburary 4th)

Dr. Bianca Williams from The Graduate Center at CUNY and Dr. Dian Squire from Loyola University Chicago share their experiences in the academy and how they were impacted, in more ways than one, by the development of their book, Plantation Politics and Campus Rebellions. By engaging in anti-racist teaching efforts, they describe the heavy cost that comes with this work, especially as it's often not supported by higher education institutions. Join us as we hear more about Drs. William and Squire's educational background, what they've learned from their journey in the academy, and their view for the future of anti-racist work.

Transcript – Episode 1

Season 3 Episode 1: Plantation Politics and Campus Rebellions

Guests: Dr. Bianca Williams & Dr. Dian Squire

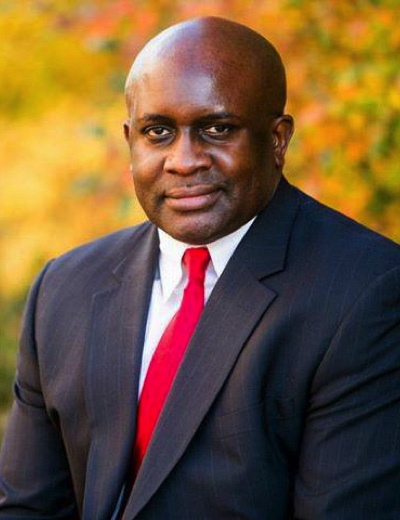

Omar: Welcome back everyone to Season 3 of the HEART Podcast! My name is Omar Romandia and I’m a second-year doctoral student studying Education Policy at the University of Connecticut. I’m so grateful to be a co-host and co-producer to take you on this exciting journey and am very grateful to kick off our third season. I’m here with my boss and colleague, Dr. Frank Tuitt, who will share a little about his role at UConn. Passing it over to you, Frank.

Frank: Thank you, Omar, and welcome back everyone! I’m Dr. Frank Tuitt and I will be co-hosting and co-producing the podcast this season while Dr. Milagros Castillo-Montoya is on sabbatical. A little about me, I’m the Chief Diversity Officer and a professor at the University of Connecticut where I teach in the Department of Educational Leadership. I’m joined by Omar, who is co-host and co-producer of the podcast.

Omar: Thanks Frank! We hope everyone had a restful winter break and are ready to engage in further exploration and learning about antiracist teaching in higher education. For this third season, we are continuing our conversation on Antiracist Teaching in Applied Fields. We are excited to engage in these conversations and hope you are too! While Dr. Milagros Castillo-Montoya is on sabbatical this calendar year, we plan to have a variety of faculty affiliates join us as co-hosts and co-producers so stay tuned!

Frank: Joining us for our conversation today is Dr. Dian Squire, who is an associate professor and the founding Associate Dean for the School of Nursing at Loyola University Chicago. Dian is a critical higher education and student affairs scholar whose work is dedicated to pursuing interdisciplinary anti-oppressive scholarship for the purposes of socially just institutional transformation.

Omar: Also joining us today is Dr. Bianca Williams, who is an Associate Professor of Anthropology, Women & Gender studies, and Critical Psychology at The Graduate Center, at CUNY. Her research interests include Black women, travel, and emotional wellness; race, gender, and equity in higher education; and Black feminist pedagogical and organizing practices. While in her role at CUNY, Bianca encourages graduate students and faculty to think broadly about the utility of public scholarship in a variety of careers, reimagining doctoral education as a process of wellness and wholeness.

Omar: Drs. Williams, Squire, and Tuitt are the co-editors of the book Plantation Politics and Campus Rebellions: Power, Diversity, and the Emancipatory Struggle in Higher Education. This volume published by SUNY Press, provides a multidisciplinary exploration of how plantation politics are embedded in the everyday workings of the universities including its curriculum, pedagogy, and more.

Omar: We would like to begin by acknowledging that the land on which we gather is the territory of the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, Eastern Pequot, Schaghticoke, Golden Hill Paugussett, Nipmuc, and Lenape Peoples, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations.

Frank: So very excited to have some really, really good colleagues and collaborators in this work with us today and happy to be joining in this co-facilitator role with my colleague, student, and just partner in the work, Omar. So, welcome to all of you. And Kelly, for helping us get organized here. I wanted to just do a quick shout out. We're going to get started here with the conversation, and in the spirit of the heart podcast, we really focused on anti-racist teaching and anti-racist pedagogy and much of my thinking around this work has been informed by both my colleagues Dian and Bianca here, I'm actually going to call you by your formal names, Dr. Squire and Dr Williams. And much of that work has really led to a series of collaborations we've had moving forward. So I want to begin this conversation by asking. Both of you to reflect a little bit on. What anti racist teaching is to you as you think about it, as you put it into practice. What do you think about it and what is it to you? And either one of you can jump in. Looks like it's been handed to Dian.

Dian: I guess I think of it, it's okay it is to me, um, actually a pretty, I think, complex form of teaching um, that is not something that you're just sort of like. “Hey, I showed up into the classroom and all of a sudden, I'm this, like, anti racist teacher, because I have good intentions,” right? Like good intentions don't lead to great outcomes sometimes. Um, so I guess one of, like, the core tenants, if you will, of anti-racist teaching for me is the centering of Black, Indigenous and other student of color voices in the class and that's in the curriculum. Obviously, that's an example that seems, like, super basic, but I think that is kind of the basic foundation of how I think about that.

Dian: The second kind of level is obviously you're taking an intersectional examination of, you know, whatever your subject is really examining power, privilege and oppression. Um, and I sort of then kind of I guess have these other pieces that I try to make sure that I'm considering throughout my practice as well, which is making sure that those students in your class Black students, other students of color actually can be heard in the space and actually understood when they're sharing their stories, or providing anecdotes or research, or whatever the case might be right that we're really listening to and understanding what is being said in front of us and not just sort of hearing words.

Dian: So, I guess those are some pieces around just sort of like listening and basic, like, inclusion to me when it comes to anti races teaching and then I think there's some sort of like, more nuanced pieces to doing the work to sort of the pedagogy pieces that are sort of happening in the moment while you're teaching the class and some of those are, um, maybe like protecting students of color from, like, racist thoughts and actions that are happening within the classroom space. So really identifying what that person said is racist maybe they don't realize it is. Let's, like, sort of unpack that a little bit, um, and ensure that the students of color feel like safe in that space, um, and ready to continue in that space.

Dian: And engage fully, right? And sometimes that might mean, like, removing the person who made that comment, um, or stopping the conversation altogether so it can kind of look different, sort of based on the situation. I think. Another part of that to me, too, is, I think, making sure that students of color feel like, they have permission to speak, I guess, in a way, you know, like, I think when we're in classroom spaces, obviously this educational systems are really set up to center like the teacher as the nowhere, right? We have this whole Freirian thing. It's not new necessarily, but in reality, right? Like, um, when a lot of students, particularly, maybe first generation college students, um, students of color, et cetera, people who are maybe newer to the space or newer to these college classroom settings, um, sometimes they feel like maybe they don't have the right to speak, um, or show up as a full person and I know that was true for me being a first generation students of color as well and sort of thinking about just like, what am I allowed to do? What can I do?

Dian: What am I allowed to be like, who can I be as, you know now a faculty member as an administrator, even though I grew up in Miami right? I grew up also in a place that doesn't have a lot of like, Asian American people even though Miami is, you know, pretty diverse in all kinds of ways. So I never had those faculty members that were Asian or teachers or anything like that and so I never knew that, like, I could speak up or that. I could be a faculty member I could, you know, be an administrator until later on in my life and so just making sure that students are not sort of Um, subsumed under, like white supremacist, notions of like, imposter syndrome, or feeling inferior in some way in the classroom. And sometimes that's what I mean by permission, I guess, like, um, making sure that they know that they belong in the space, they've worked hard to be in the space, they've done just as much if not more than other people to be in that space. Um, so some of it is sort of that, like, interpersonal component as well. There's lots of things but I'll stop there.

Frank: I appreciate that. And I want to come back to some of your notions around safety and creating space and prioritizing voice. Bianca.

Bianca: So, I think Dian and I share some similar kind of principles and approaches, um. Specifically for me, and I've written about radical honesty and one of the books that, um, Frank has edited with Taylor Haynes and Saran Stewart. What is the name of the book Frank?

Frank: Race, Equity, and the Learning Environment

Bianca: Thank you. Because I know folks may want to go and read the excellent chapters that are in that book from all over the globe. So, if you're interested in anti-racist teaching inclusive pedagogy, I would invite you to read that book. But I wrote a chapter on radical honesty, which I think is my anti racist approach to the classroom both like, the pedagogy, the theory behind it and the actual method and for me that comes from centering Black folks in the classroom, particularly Black women, CIS and trans and it comes from my training and Black studies in kind of studies, Caribbean studies and anthropology and women and gender studies. So I center Black feminist theory and all my courses, regardless of what the topic is. Um, with the awareness the anti-racist teaching is part of that canon and so radical honesty specifically is about 4 things is kind of focused on 1. it's an awareness that the classroom is a political space, and that higher ed is a white supremacist, patriarchal transphobic, homophobic space and so if we're in the classroom, then we're in all of that. And we have to be kind of explicit and aware of how those structures and oppression affect what's happening in the classroom. So that's the first thing. The classroom is a political space, it is a gender making and race making space and to be aware of that.

Bianca: The second thing an an anthropologist, what drew me to anthropology was the valuing personal narrative and personal experience and so in my classroom, as a part of my anti-racist teaching, uh, valuing all the personal experience that we bring to the classroom and using it as a case study as part of the work that we do. So, it's not opinion, right? It's not just I went to this public school and it was racist, because I experienced this, but it's I experienced this and let's figure out what factors created the environment that allowed you to experience that, right? So, connecting students, personal experience and my personal experience with the texts that we're reading, and the theory that we're making, um, personal narrative, allowing students to write about their lives and use the critical tools that we're learning and creating to assess what's happening. And so, you know, sometimes we get questions. Um, I know the 1st generation student, I had a question, like, can I use I in the essay or in the paper right?

Bianca: Like, in my classroom that's encouraged, because I, as a central location of where analysis can happen, right? So, personal narrative is essential to theory making and those two things are not separate or, you know, um, experience as part of what the theory making processes. And then the last thing is, um that emotion is a form of knowledge that can be a form of raw data that can be created that can be utilized to create knowledge. And so in an institution where, um, intellect is often talked about as, like, rational and neutral, and not emotional for me anti-racist theory, particularly because of the gendered and the fem this lens I bring in emotion it's actually central to how we create meaning and analysis of the world, so by censoring Black women by censoring Black people if you go into any barber shop, which Melissa Harris Perry has studied, if you think about the theory that you learned from your mom and your grandma, when they were analyzing white supremacy in their neighborhoods, like blank would say, the worst of white folks, right? Those are theories and they come from feelings and narrative and experience and so in my classroom emotion is central to how we create knowledge.

Frank: Appreciate that. You both touched on this a little bit. And so I want to circle back. But could you say a little bit more about what was the genesis for sort of thinking about anti-racist teaching? Both of you have been doing this work before it was cool to do it, right? So what was the genesis for it? What got you interested in thinking about conceptualizing, whether it's radical honesty or Dian I know some of your earlier work around inclusive teaching more broadly. What was the impetus for that?

Bianca: So I would just say off before we respond to your actual question, it might be cool to do it, but it would be nice to have it resourced and valued as part of the promotion process in higher ed. So, I'll just say that off the top. We may do it and it's cool and it's useful and effective and our students love it and our colleagues may love it, but it would be nice structurally, if it was actually valued. Um, so this came from at least from you radical honesty and thinking deeply about anti-racist and feminist ways of teaching came from being a student in higher ed, first generation, African, American and Jamaican, uh, working class, um now, kind of hesitantly middle class and figure out what that means. Um, Christian, uh, heterosexual, like all of my identities, right? Trying to figure out how to navigate both the physical space of higher ed and the culture of what it means to be an undergrad and graduate student at a pretty elite and predominantly white institutions that was first, it was my experience that led me to think deeply about why was I feeling the way that I was feeling as I was learning the things that I was learning and somehow the things I was learning what that were critical, like, analysis of race and gender, or weren't lining up with how necessarily I was being taught or necessarily what was happening in the campus environment so sometimes I had a great teachers, but the rest of my environment felt terrible.

Bianca: So when I decided to be a professor, particularly the University of Colorado, which I knew was, like, I don't know maybe 1%, Black at 30,000 students. I knew that being a Black professor on that campus meant that my race in particular was going to be very present and I wanted to figure out a way to teach that was genuinely me; that I didn't have to put on a performance. And we all do it, professors, we have performances, but I wanted to be able to bring my whole self to the classroom if I chose to, and to be able to teach through that. And so that's what led me to anti racist teaching, wanting me to be comfortable in the classroom and wanting my students to be comfortable and have a process where they can be affirmed in the classroom.

Dian: Similar but different. Uh, uh, you know, it does. I think it did stem from you know, obviously my upbringing, my identities, um. But in the sense that I don't think I ever really understood what it meant to be an Asian American person. Um, and so, even though I always you know, I guess identified as Vietnamese, you know, cause my mom's side of the family is and I am, uh, as well, but it was never really spoken about and our, you know, the immigration story was never really share, the language wasn't spoken in our home, um, my mom really tried to like, Americanize herself and there for us. Um, and also I never once again, saw myself really in the classroom space, or even in really the community where I, you know, where I lived.

Dian: I had one of my best friends, an Asian woman, Korean woman, and we would always just say, like, we were brother and sister, and, like, people believed us ‘cause there were so, like, few Asian people in the school that we could just say that and it was like, true. So I don't think I really came to really think about anti-racist teaching until I kind of moved into, uh, obviously like graduate school, particularly like my PhD program. Um, where I really had the chance to just, like, think about all of that um, and think about it alongside you know, my peers were all men of color, mostly queer men of color, like, inside our cohort and really just sort of explain like we're explore kind of what it meant to be the queer, man of color, like, in higher education in society, um, in relation to other other people. Um, and then, sort of from that point, you know, maybe quote unquote becoming just a little bit more, like, radicalized around this topic and being, like, I don't care what people think about me and how I teach like, I'm going to teach about these topics I'm gonna teach about race and racism, and I'm going to tell people what I think about it, and we're gonna read books about it and I don't care what my evaluations say we're going to, you know, do all the things that we talked about in the first question, right?

Dian: And, you know, I don't know if that's like, the best way to go about doing this work or getting interested in doing it. But it's what I did. And it's what I, you know, what I live with. And, um, I think for me, it's more important that my students of color felt seen in the classroom space that they that they were able to read about themselves as early as possible and have those conversations and, you know, like Bianca said, like, show emotion and, you know, do all of that work as soon as possible like, as soon as they had, you know, their first person of color, their first Black professor in graduate school, you know, whoever it might have been, um, in the places that I worked. Um, I guess that sort of experience is sort of what led me to teach in this way and for me, it's just sort of maybe initially, it was something that I made. Sure, I was very intentional about practicing, right?

Dian: Like, I'm going to do try this thing or this set of, um, things this semester and see what works and then I'm going to keep testing them and kind of molding them to what I'm learning and who the students are and kind of how maybe that practice functioned um until I get it right you know, and for me, it always sort of took, like, a couple of years of teaching a class to make sure that I felt like I had that syllabus that made the most sense that I had those, um, assignments that, you know, centered all of those pieces of motion and life and, um, also the academics and the books that were reading and whatever it might be, um, and now that I've been teaching now for, well, post grads since 2015, but I've been teaching undergraduates since 2005. I feel like I'm just sort of naturally do those things now it's just part of who you are, um, you sort of live with those, those components of anti versus teaching that Bianca and I spoke about.

Frank: Yeah, I love the connection between identity and pedagogy that you are both making. So, it raises this question, and we talked a little bit about this in other spaces. But what's the cost of showing up in the classroom the way you do? What's the cost of engaging in anti-racist pedagogy?

Bianca: Yeah, I think there are a lot of costs so I said earlier that for me, I really wanted to be able to bring my whole self to the classroom and bring all the parts of me that I wanted to be present, um, because I felt like graduate school was such a hazing process and socialization process where I had, like, parts of myself were broken up, or I wasn't allowed to show parts of myself in this goal of becoming a scholar, right? Like, certain parts of myself were, I was penalized or, like, they were shunned by folks and so I wanted my teaching experience to be different as a professor. What I've learned from my undergrads and my graduate students, you know, time changes everything I think even, I mean, I'm not that old I'm still pretty young, but a lot has changed in the past, even decade and a half, and even the past five years, and particularly in last five years since the Movement for Black Lives.

Bianca: What I hear from my undergraduate and my grad students, particularly my grad students who are instructors is, “I don't want to bring my whole self to the classroom.” Like, they’re like, “the institution of higher ed does not deserve my whole self, that actually great costs come with bringing all of who I am to the space,” and so I think some of the costs are when you're a person of color, when you're a person who is marginalized in structural ways in higher ed, and you show up authentically and fully yourself, you know? It's not only great critique, but there can be great pushback, resistance, various forms of like, punishment for bringing who you are, and I, when I talked to grad students about radical honesty and inclusive pedagogy, I also hear that grassroots don't have the same power that we have as tenured faculty or tenure track faculty, right? So figuring out how to do anti-racist, teaching, figuring out how to push the students in the class, or just espousing white supremacy in that position, when you have such little power as a instructor is really difficult and so there are a variety of costs that can happen, um, depending on your position now. So, I think it's important to, yes, bring up identity.

Bianca: But there's also the awareness of positionality and power, right? And that different instructors, different people standing in front of the classroom, or sitting in a circle in the classroom, have different costs that they're going to experience in doing this work.

Dian: Yeah, that's, you know, snaps for all that. And I think, Frank, when we started the Plantation Politics project you asked me, right? Like, you're at that point I wasn't even on the tenure track, right? Like, are you okay with doing this work? Like, have you thought about what it means? Um, I think you were maybe pre-tenure at that point and, you know, as I said, I started just like, after grad school, I was just like, yeah, I don't like I don't care what people are going to think about me and what I want to say, like, I want to say the things that matter. Um, but I think, you know, now, what is it six years later? Like, it has had really, I think, detrimental impact on my life. And so, you know, it's definitely not rosy, right? So, like after I left Denver and the postdoc, um, I went to Iowa State University.

Dian: And, it seems really minor, but that was when we were sort of really ramping up Plantation Politics, like, presenting it, publishing on it and all that kind of stuff, right? So, I was, it was also just like a big part of my research identity like, what we were doing just in general and so I was talking about it a lot. And, um, it seems like menial, but every new faculty member at Iowa State gets like a story in the newsletter in the School of Education newsletter right? And it goes out to, you know, whoever's on that listserv. I did the photoshoot, I did the interview, it was laid out, I looked at proofs, and then it was pulled as soon as, like, the dean learned about what I was writing about Plantation Politics and there, you know, there's some other stuff happening too. They were like, what was the department head they called her but, um, we were hiring a new dean for the entire, uh, depart, uh, health and human services piece and, um, we're also hiring a new president at that point and so they didn't want to, like, write a story about somebody calling universities plantations. They didn't want that out there as, like the image.

Dian: Um, so, you know, that was like the first piece where I was, like, okay, like, I'm super pissed about this but, like, whatever, it's a story, people know who I am still like, that's that's, you know what I'm about the next year, you know, they're hiring for a tenure track job, and I'm just a visiting on a two-year contract at this point. I don't even get an interview, right, for this position and I have pretty much perfect teaching evaluations. I've had them my entire career. Um, you know, I'm obviously like publishing, like, crazy presenting, you know, everywhere. And I don't even get an interview for it, right? And so I'm like, okay, well, they clearly, like, don't want me here. Everybody gets an interview. If you're a visiting professor pretty much at the institution that you're at. Like, if you don't get one, something is wrong. So clearly something was wrong, right?

Dian: And I wanted to leave anyway, um, as I do not like Iowa. Um, but it's sort of, I think it's in some ways, it like, stunted my career a bit right? ‘Cause I started on the tenure track later it sort of made me, it really hit me personally, right? Like, I went into a really, um, deep depression that I'm still dealing with and it started that year. Um and then, I, you know, I just had to leave and I took another job. That wasn't really great for me either. And it was a tenure track job but it was in the middle of nowhere. It was mainly, you know, white folks in the school. A dean, who just didn't get what I was doing. No critical scholars in the entire school, but I just had to get out. And so I felt like that also sort of stunted my professional development. And because it also stunted my personal health, my mental health and physical health, and all of those pieces that then also negatively impacted. My professional, like career, and my ability to just focus on things.

Dian: So I'm basically just saying that, like when you do this work, there can be really negative impacts, not just on sort of um, an evaluation or somebody valuing that you, you know, teach through an anti-racist framework, but really on like your whole self. Um, and this past year. It's really what led me to essentially, like, leaving the field if you will like, I'm not technically in higher ed and student affairs anymore. I don't teach those classes. I'm just finishing some projects in that space that I kind of don't even want to finish and now I'm kind of an administrator role where I get to just kind of, like, do my own thing. Um, and I don't have to be bothered by all that stuff. I'm not tenured, I am on the tenure track, but you know, I'm also in a whole different discipline it's just, you know, it's, it's been this kind of like, weird, windy life that I've lived in the last few years that have really negatively impacted like, who I am, what I think about the academy, what I think about research, the worth of it all, like, Bianca said, like, how much I give to it, you know? I show up and I leave.

Dian: I show up at the time, I'm supposed to show up and I leave at the time. I want to leave, right? I don't care if I'm doing… I'm not giving my life to this job. I'm giving my time that I'm paid for to this position, and if it doesn't get done, it doesn't get done until the next day. And don't text me after hours, right? Like and I let people know that, like, that's the life I want to live now but that was the result of I don't know, maybe giving up hope right? Like, giving up all that stuff that I told people to have and not being able to do it myself right? But because of the kind of everything that was happening around me. So, you know, that's where I am at this point.

Bianca: I guess can I say something real quick? Yeah, I know you might want to transition Frank, but, um, I just want to say real quick that so many, like, I feel in right now, I'm definitely in the space where he is and also, I think so many of the folks that I know that are deeply invested in anti-racist teaching leadership like justice, transforming, higher ed, especially during the pandemic, especially in the past two years. So many of us are so burnt out from everything that is happening, because some of the burn out that people are experiencing now, we've been doing for almost our entire career in higher ed, right? So, like, the constant awareness of all of the impressions that are operating the constant trying to, you know, if not prove yourself worthy, but, like, be like, I belong here.

Bianca: The constant wanting desire to make it better for the people behind you and, like, create space for things that you didn't like that weren't made for you. I think we experienced the burn out. And so I just wanted to name the emotional costs of this work, because I think it's something that's so often belittled, even in spaces where people take mental and emotional wellness seriously. We haven't come up with really good, not even tools or techniques for, like, wellness, but like structural ways of talking about and dealing with the emotional impact of doing anti-racist work and white supremacist spaces. And it has only been heightened in the past 2 years. And since we have no idea when this moment of the pandemic, or when this is really kind of explicit and spectacular moment of police violence will be going away. Like, we're, we're just kind of in a, in a holding pattern and it's taking that's the emotional cost. We can talk about the wins and victories later, but I wanted to emphasize and affirm and support Dian’s story.

Dian: Yeah, and especially if you're the only one, right? Like, at NAU (Northern Arizona University), I was the only one. I was doing basically this job for free, and also getting paid nothing, but also trying to try and, you know, we always say, like, people would probably have to do, like two times as much to get half as far. I was trying to do like four times as much to get started, you know, and nobody gave a s***. Sorry, I don't know if we can curse. Nobody cared that I was doing that in that school, right? Like, people cared my friends care the people in the field care, you know, quote, unquote cared, whatever, right? But, like, where I was trying to go with my professional career, nobody cared.

Dian: And that can only last so long before you're like, “I’ve got to get out of here.” And, you know, I would have I had probably four times as many publications to get tenure at than I needed. I would be a full professor, like, twice there. Um, and I gave that up to leave because it wasn't healthy in any way. And so now I'm just sort of in this limbo space.

Frank: I actually want to stay with this theme around the emotional cost. Um, it's one that I don't think the three of us have talked about in relationship together, I'm sure they've been individual conversations, but as the editors of this project and the contributors of the Plantation Politics, which we’ll come back and unpack later. I don't think we've got a chance to talk about the cost of it and from the perspective of you know, the labor from the perspective of it, not being valued. I think I want to add one other dimension to it, which is, uh, the cost of diving deeply into work that you've committed to doing and at least for me how that process uh, exposes the ways in which we’re being exploited, right? And then having to reconcile that, right? So, as you know, my part in, uh, in the chapter is about the CDO role and the ways in which I was both writing about it, living in it ,and reconciling the ways in which I was complicit in some of the very things I was trying to disrupt. And how that became a regular part of my engagement with my therapist around, “how do I make sense?” I think we don't give enough attention to this, uh, um, the cost of doing anti-racist work. I know for a fact, our institutions don't. They don't want to count for it as a part of the labor. They haven't figured out how to support folks in doing this labor. Or, as Dian lived out in his situation. It's not valued. So, I guess for the folks who are listening to this podcast. What suggestions do we have for them, because this work is not going to go away. You both have talked about various strategies, whether it's don't text me after five. Bianca you, and I have talked about who you're accepting invitations from now to engage in this for it. So, what are some strategies, uh, that you would offer the folks about this? How to navigate this?

Bianca: Yeah, so, what's your referencing is for me a huge like, I don't know what happened on this day, but a huge breaking moment for me was January 6th. Like, I remember sitting at my computer and I was probably working on a paper or something. I was writing something and Twitter, like, exploded with what was happening at the Capitol, and I turned on a TV and something about the images of white folks in their true entitlement and audacity, going to D.C. and just taking up space and entering spaces that I knew as someone who organized with my chapter in Denver as someone who has participated in public demonstrations of resistance and social action that if me, and even ten of my colleagues or my comrades from had done any of that we would have been shot or arrested in the street. Something about that disconnect between the globe, watching white privilege and white supremacy and action and people just standing by and letting it happen or facilitating it.

Bianca: Like, there was a break and I remember and it was also the moment where, like, all of our institutions were coming out with their statements about supporting BLM, like, show me the money. Like, this means nothing to me because at this point I've been doing this organizing work with collectives for so long and the statement doesn't do anything for me. Your cluster hires that will disappear in five years don't mean anything to me. Like, show me where your real commitment is, and in that moment. It was like all of the work that I had done, I just couldn't do it anymore. Like, I couldn't. Literally my physical body. In this moment shuts down when I think about doing that work because I realized how much time and energy it cause it took me to be in the room with folks to teach them about their white supremacy and to hope and, like try to teach tools to be particularly whiteboard, better white folks with a white racial, like a white anti-racist consciousness and to know that's so many of those folks who were in D.C. doing what they were doing, right?

Bianca: Like, that my hours and decades of labor probably meant something to a few people, and I'm like that that's valuable to me. And that structurally or in the long term, it doesn't feel like it did enough. And so literally on that day, and since that day I have actively decided no. Yeah, no, I'm only investing my time and energy and spaces that sensor black folks. Like, I just can't do it anymore. If black folks are not central to this thing, that I'm probably not going to do it anymore. And it's a bit hard to be honest. There was, um, uh, I don't know if grief is the right word, but it was an identity shift in some ways, and it was a commitment shift in some ways. Because when I went to Colorado, I knew Colorado. Colorado is a white state. Colorado State was a very white university. I knew I was going to teach Anthropology and Black Studies. I knew what I was walking into, I didn't walk in without an awareness of what was happening, but I also felt like I had the tools and the capacity to be a person who could, to be honest, how white folks do better. Like, I knew that me living safely and the people I love being in a safer world required white people to do something about white supremacy and some of us have the capacity and skills and ability to do that sometimes but I had reached the end of my capacity that the emotional cost of it, the career costs of it and just frankly, the anger and rage like, I just don't have that patience anymore. And so I'm ready to pass that baton to whomever else would like to do it and can do it and has the resources to do it. But for me, people have to be present and centered for me to do the work now.

Dian: Yeah, I feel that too. I don't know if January 6th was like that moment necessarily, but it's just sort of another moment in time that just kind of reminds you where we're actually at, and, um, obviously I transitioned to this job pretty soon after that, um, or the summer after that happened and um, I sort of take a similar stance. I think, you know, there's obviously people in every institution who are sort of like the cream of the crop of like, white supremacy, you know, like the ones that you get hired to really like, work on. And while I'm not going to, like dehumanize them and throw them, you know, to the wayside. I've actually decided to not spend my time on them because they are a minority in the school, right? Like, even though the whole school here might the school of nursing that I worked in might not, um get everything I think there are a lot of people who want to learn and want to change. And then there are those few that just don't care that I'm here and will do whatever they can to make sure. I'm not here as soon as possible.

Dian: And so I'd rather not spend my energy on them, but spend that time with people who want to be here, who want to have these discussions um, really supporting the students of color um, the very few faculty of color that we have the two or three staff members of color we have, right? Like, doing work with them, spending time with them, building relationships with them. That, to me is kind of like, where I'm more interested in spending my time these days. And also, like I said earlier, just sort of not doing anything that I don't like, want to do, or that takes energy that I don't want to give especially giving it to people who I don't want to give it to. It seems kind of, I don't know, it feels so wrong to say that, right? Like, that's not what I feel like have been like, my values, the way that I've worked for the last, you know, seven years of my life. Or even sometimes, like, what I teach my students sometimes. But I feel like for me now it is sort of like passing the baton and hopefully maybe like teaching some of those lessons that I learned to other people who have that energy, or just have a different set of skills or desires or whatever it might be to do that work. Um, because I just don't always want to do that work anymore, you know, like it does feel like I do. Okay. I'm really bad with the motion so I actually don't know what it feels. I just have to pull up a list of emotions and, you know, like, I'm, I am a little bit like, irritated with myself that I wasn't able to like, hang in there fully, right? I obviously mentioned I felt, like, really depressed. A lot, a lot of my life, you know, the last five years, um, really like, uncertain about, like, what's next you know, for me in my career, but also just my life like, you know, am I even going to stay in the academy or not? All of those things are coming up to me as I sort of think about like, “how did I, how did I survive and how am I, like, surviving now? And am I thriving?” It feels very, like capitalistic but, like, I feel like if that's the way the world functions, then, like, it's some level, I also need to function in that way because it will just continue to extract from you and I think, like, I've heard that narrative from a lot of people who have been in the field longer and done this work longer.

Dian: And I, like, I'm at the point where I get it now, you know um, and so I'm still trying to find out like, “what am I really inspired by? What am I really motivated by? Like what's going to get me up in the morning? What am I passionate about?” And that's like a whole different, like, part of doing this work that I haven't fully figured out yet.

Frank: So, I absolutely appreciate some of the jewels you are all passing here. I was thinking about this notion of “know your capacity,” and “pay attention to your own sort of sense of health in this work,” right? Setting limits on your engagement and how you use your energy. Empowering others to lead and do the work. So, this notion of passing the baton and then Dian, you ended with feeding your passion and I think all of those things are things I've tried to, in my own work, um, be better about. I absolutely, uh, do not check emails on the weekends now. I don't have my work, um, on my phone, my work email on my phone, so if there's an emergency, someone's gonna have to text me and let me know about it ‘cause I'm not checking my phone or emails on the weekend. So, these boundaries are things that help, um to allow us to do a better job of taking care of ourselves.

Frank: The one thing I'll add that, I think was a little helpful for me is I found some healthy ways to release my rage that was, um, you know, coming from this engagement and so if you look at some of my more recent writings, you will see, uh, a much more focused, uh, energy and criticality in in, in those writings, and that was a form of release from me. It's definitely much more personal running. And then, I suspect I benefit from being where I am in my career that I can now choose, um, more intently what I'm going to write about, as opposed to writing for you know, 10 year are writing for publication, but I found those those last set of writings that I engaged in to be really helpful in releasing some of the range that built up over the over the time. Uh, I know what we're getting close to time. We didn't want to make a shift back to sort of how this work benefits our students and so, uh, I'm going to invite Omar to take us through these last couple of minutes we have with some final questions for us.

Omar: Awesome. Thank you so much, Frank and thank you so much Bianca and Dian for your honesty and your heartfelt experiences through this process. I think, you know, I really want to give a shout out to Frank and all of you thus far, just for expressing the reality in this process of practicing anti-racist teaching. As Frank alluded to, it’s not supported and it must be like a breath of fresh air for our audience to hear about this issue. Um, and so something I'm curious about just as a student in this process is how, how students respond to your approach to anti-racist teaching. And I think, a couple months ago, actually, I turned thirty and I didn't think when I was a year ago when I was twenty-nine, I was like, “oh, I'm not gonna feel the shift as much, it's not gonna be as intense,” but sure enough that decade, that three in front of the year is definitely a marked difference. And so, I'm just curious, all of you as scholars as practitioners, um, as professionals, like, what do you see and what do you all feel is on the horizon for the next generation of scholars and activists and how does that inform the way that you instruct your students? Bianca, do you mind getting us started with this question?

Bianca: Sure, that's a really good question. I've been working on a book about pedagogy, organizing and organizing as pedagogy coming from, um, trying to tease out the lessons I learned like teaching the stuff that I teach in the way that I teach during these last few years, since the Movement for Black Lives, and also organizing, and being one of the kind of educated educator centered folks in my chapter of BLM and again, it's interesting because the last five or six years, or so much has changed like, our language has changed our awareness of new frameworks and new visions for the future. I mean, if you had told me two years ago we were going to have a national conversation about abolition openly I would have been like, “you are out of your mind.” Um, and so much has changed. Um, and I think. So, we haven't even defined Plantation Politics. Like, so, we wrote this book because so much of what was happening in 2015, and the year's following was an awareness for a lot of people how deeply connected how deeply connected the power dynamics and the engines that make higher ed go are connected to these kind of previous moments of plantation life and culture.

Bianca: And so our argument in the book is that you can tease out really important connections between, um, plantation life and culture from the past and how the institutions that we work at, where are both established and continue to operate and that the exploitation of folks of color, but particularly like Black people in a particular way, like Black life, like death, Black labor, Black emotion, um, Black leadership, right? How is exploited and utilized to keep the university running. Um, and so this next generation, what what I love about being in the classroom with my students, um, is that they are growing up and grew up in this moment of movement, building and protests, and they're bringing what they learned in the streets, in the neighborhoods, in their public schools, and their private schools to their training and this moment. And that there’s a long history of activism in higher ed that has led and leads faculty and staff in doing transformative practices on campus. I’m not sure how much I’m teaching them but I think we’re all learning and teaching together to create new world and what the tools will be in the next 10 years, in the next 50 years. So that was a kind of unwieldy answer, but I think it's what I do, hoping that I can give the students tools to think about things a little bit differently and then they respond and teach me in the classroom. And they push me, right? Like, what we thought was radical 5 years ago is not really radical anymore. So they challenged me to think differently and deeply.

Dian: Yeah, and I mean, I'll just ditto that. Um, it's, I think it's aligned very similar to the way I teach, you know, I always try to start my courses with just history lessons, I guess, and even when I do presentations to campuses or whoever it is, it's always sort of like. Here's what Settler Colonialism is. Like, here are some of the main technologies and domination and here's how they're still showing up today. And, like, I was the opposite of and here are some frameworks for how we might understand what's going on today. Now, like what do you want to do about it? Like, what do you want to do with this information? You know, I didn't think I was that old, but now, like, I am getting older and, like, I am much older than the students. If I teach undergrad, like the undergraduate students that I'm teaching, right? Like twenty years.

Dian: That's like, that's a million lifetimes in today's world. And so, like, who am I to really say, you know, this is the one way you should do it or do anything, but I can say, like, here's what I do know. Here's what I know about the history. Here's how I know how we got here. Here are some ways that I think about it, like. What do you want to do? How do you want to extend off of that work and you know, um, it's, you know, it's providing the toolbox, right? Like using that metaphor. It's just providing the toolbox for students. So then go out and do what they, um feel is needed in the world and so yeah, you know. I mean, I think I can keep up sometimes, but then there's always just something new, right? And I think that’s really great, right? That's good progress to be making.

Frank: I love the focus on how we learn from our students. I think that's one of the reasons I continue to teach and I’m a few years older than everyone on this call. I'm equally amazed at how much things have changed in the time that I've been in the academy. And so anti-racist eaching and Plantation Politics is, you know, for me a project to help unleash. I've been thinking about it this way more recently, unleash the mass liberatory imagination of our students because we have so much to learn and that creates so many different possibilities for reimagining what these spaces can be like. I will admit it's hard, as someone who and that's something that, that's been a challenge, but I've, I've gotten more used to it over time. I think as as we're nearing the end, you know, one of the questions we were thinking about is, how do we see Plantation Politics as a, sort of anti-racist project? I think it's clear that it is, um, and it's interesting because it grew out of a really pivotal time as beyond convention, but in some ways, I think predated what was about to come, right?

Frank: And so we had no idea that the country would be once again embroiled. In the way it was around the killing of Black bodies, Black folks, uh, left and right. And so the Plantation Politics is absolutely a tool that we hope folks can use to find these new ways of deconstructing, dismantling, destroying, uh, whatever the appropriate response is, to some of the existing or persisting remnants of our plantation pass. I wonder for, I guess, just final thoughts about how you see Plantation Politics as an anti-racist project and what possibilities perhaps exists, uh, that moving forward in the future for for this work. It's something we've talked about a little bit, but you know, when we haven't, we haven't answered yet. I would, I would say so I'm curious to hear your thoughts about that.

Dian: Um, yeah, I mean, obviously there's a deep alignment, I think, you know, obviously there's sort of like the academic take, so you can read the chapters and you can kind of do that kind of analysis. Um. We've read the chapters many times. Like, sometimes your brain's just like, okay, I'm done with that. Um, but I think for me, um, it does a few things. Maybe more like an interpersonal level if you will, um, it helps me to understand, like, what sorts of logics we utilize when interacting with people obviously. It helps me understand, maybe behavior, right? Like, why somebody does something they do or doesn't want to do something that they don't want to do? Um, I think it can, um, help provide certain levels of, like, grace and empathy, right? And interacting particularly with Black people on campus. So, for me, those, like, interpersonal pieces, as I'm trying to, like, get out of my like, totally logical mind is really important for me, right? And maybe grasping more onto that emotional piece that behind to talk more about and write about and think about. So, for me, I think that that's a lot of what it helps me to do and it always just sort of reminds me, like, how deeply embedded these, these, like, plantation logics are embedded in our world and, you know, I mean, obviously just the name can just trigger something and say, like, this is so messed up like how can my analysis be even more critical and more intentional about what I'm doing above, and beyond any sort of other, maybe analysis that I'm engaging in or framework that I'm utilizing.

Bianca: Um. Hmm, I think, you know, there's so much good stuff happening in this moment, even in this moment where a lot of us are feeling a lot of tough emotions like, when I watch a grad student led union organizing that is happening on campuses. And, like, pay equity conversations that are happening in labor conversations when I watch the still happening on campuses and in various streets, like protests against police violence, you know, for me, those campus rebellion are the victories like, when you were asking about the costs of this work, like me, seeing participating, affirming, supporting, helping, make room for covering when possible the students who are driving that work and driving the creation of more radical futures, like, those are the victories and so while people may look at the title of our book and think the rebellion part is like a sad part or a part we should run away from I think what we're arguing in that book is that universities should really embrace those campus rebellion and take them as moments to assess like, their mission statements, and, like, if they're actually doing the things that they say they want to do, right?

Bianca: The gift of Plantation Politics as a framework and I, I was about to say, and I'm glad Dian said it. This grace part is really important. And I know some of the students listening might be like, this is the part they might get annoyed with me about. But so, many of my colleagues, particularly my women of color colleagues, particularly my black women scholar colleagues have been having the conversation in the past four years of the lack of grace that we experience. From our Black students, for our students of color, and I think what happens is the plantation policies framework can really provide people who are located in a higher ed to understand a different position now and different access to power resources that we all have like, when are students actually the most powerful group to make change? When are staff and faculty and administrators, like there is an analysis to that? And if you're going to engage in organizing in these spaces, I think this framework can help, you understand, what are some of the restrictions that people like faculty have for a variety of reasons? And what are some of the restrictions that undergrad and graduate students and continuing faculty have? So, using it as a tool to really not just, and I use just quote “do activism,” but to sit down and understand the institution, and how it works, how it makes money how it functions, how it punishes people that rebel and understand our different positionalities so that we can utilize the gift of our different positionalities and that requires a profound amount of grace from all of us.

Bianca: But sometimes I want my students to recognize, like, how limited or how, what the strings are that were constrained by where the chains are that were constrained by a not like not to be literal, but, as you go higher up, you begin to have a different analysis of what the landscape is, right? And what you're operating in, and sometimes I need them to trust us, like, trust in our commitment as we can trust them and their commitment, and have grace for them.

Frank: Thank you both. Omar has already commented on the honesty and deep appreciation for sharing your thoughts and reflections about this important work and I just wanted to add to that. I think one of the unexpected gifts of this conversation was the ability to reflect on a project that I know we all gave a tremendous amount of ourselves to, and to have the opportunity to reflect and and think about the ways in which that work in particular impacted. This was not somewhere I expected us to go, but very much appreciate having had the opportunity to do that. So I very much appreciate that. And look forward to our continued collaborations, whatever shape or form that takes. Thank you very much.

Omar: Thank you Dr. Williams and Dr. Squire for being honest and vulnerable when speaking about the multi-layered cost that comes with this work. We’re incredibly grateful for the tools you shared with us today and the reminder that activism, in all its capacities, ought to be celebrated, because it has the potential to bring about equitable change.

Milagros: As always, we are grateful for the support of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning and the Office for Diversity and Inclusion, because it takes a village and it takes heart.

SEASON 2

Antiracist Teaching Through Music (October 29)

Dr. Joseph Abramo from the University of Connecticut and Dr. Joyce McCall from Arizona State University share their perspective on what it means to teach music and music teachers in a way that honors the history and totality of musical genres. Pulling from their own experience and passion for the field, they share new ways of teaching and learning with students that are both bold and humanistic. Join us as we hear more about Joseph and Joyce's work, their musical background and exposure, and their contributions to higher education through music.

Transcript – Episode 1 Part 1

Speaker 1:

Truth. I'm wondering if you could share with us your thoughts on what anti-racist teaching means to you.

Speaker 2:

Absolutely. And thank you so much once again for the invitation and I'll just get to the point. Um, what anti-racist teaching means to me, as it relates specifically to African dance is, um, the way we try to situate our work is looking at the history and the master narratives that have been presented in the world about people of African descent and in African people. So for example, um, there is this idea that Africa has no history because a lot of the history isn't documented. So you would find some of these ideas, um, echo by, uh, prominent scholars like Hagle. And, um, you will see that this narrative has been created a very racist narrative, um, a narrative that was created as a rationale for colonialism and enslavement. So that's like one part of the work is recognizing what that master narrative is, right. And recognizing that within the European and the Western construct, if something isn't documented, then it's not important.

Speaker 2:

And therefore you don't have a history. And Africa has this rich, rich history of oral tradition, and that's how we're situating our work because African dance falls under, um, an oral tradition. And then the second part of that, um, as we think about these master narratives is also, um, the experience of African diets for a people. So, um, specifically the transatlantic slave trade. So we know that, um, mostly people from the west coast of Africa were trafficked to the Americas and that group of people, which I often refer to as African diaspora, people who were scattered throughout the Americas, there isn't another narrative that they don't have a history because they were cut off from their family structures and culture and history. So we're situating dance within that. Um, particularly looking at it as an oral tradition that people of African descent, no matter where they ended up on the diaspora in north America, south America in the Caribbean, there's this tradition of always sort of maintaining sort of the African extended through our arts that is very clearly illustrated through the arts and in particular.

Speaker 2:

And we're interested in that, that tradition and how it's preserved and how that tradition speaks that to these dominant ideas that people of African descent don't have a history. And when you make a claim that profound, um, you're basically saying a group of people have not made contributions to the world. They have not. Um, they have not completely come into there to themselves as a whole. So, um, we recognize that as being deeply, deeply racist. Um, but we use African dance as a way of continuing this oral tradition that hasn't been counted within this Western and Eurocentric construct of what history is and what it means to document history. So that's how we're situating our work

Speaker 1:

True. That's, that's really powerful and a, a really interesting, um, and important perspective about recentering the person, you know, the angle, the entry point from which you're looking at history, right? Because then it begins to, um, highlight different components. And when you start with the people, you know, history, you know, was there and these traditions were already there including that. And so I really appreciate that perspective on MTV says teaching through dance, Shani, I'm wondering you want to add something. Do you have a different thought or something you want to contribute to? What does anti-racist teaching mean for you specifically around dance?

Speaker 3:

Sure, absolutely. I, um, I'm thinking about the ways in which, uh, truth is talking about this master narrative that's, that's rooted, um, and your central, your centric aesthetics, right? And so how this plays out first, like in our bodies, right? Mentally, physically, even psychologically the impact that it's had on us. And so what it means for me, especially as a dancer and as an artist who has trained particularly here in the Americas, um, where, um, most of the curriculum around dance and what we're learning is rooted in that. And so for me, it's the taking a stance, being able to take a stance, being able to send her my work around African and black folks from the diaspora centering those voices, sintering, um, the narratives of, um, African and black people across the diaspora. Right? And so it's also this, um, this agency that is created to turn back into our bodies, right?

Speaker 3:

To realize different sensibilities that we have, that we may have learned that was different in terms of how we're, um, kind of valuing our own, um, ourselves inside, inside of whiteness or inside of white excellence, that, that becomes the standard within all of this. But this practice of, um, you know, anti-racism in, in the body is really about for me, um, turning to, um, the body, the mind and the soul back to, to the roots and, and us creating our own spaces, um, to be able to, um, to liberate ourselves right outside of this, the standard of whiteness outside of this, this white gaze. And so that's kind of what I would add to it. It plays out a lot in dance in the field of dance because the master narrative is, um, the forms of dance, the techniques that are valued, right. That, you know, ballet is at the top, you know, and I loved ballet.

Speaker 3:

I had to train a lot in ballet, but, um, but it plays out in terms of one, um, us, um, using this word as it resistance in higher education, to be able to debunk some of these ideas about even technique, right? So west African dance, as well as other dancers of the Aspen African diaspora, um, has been through a journey of trying to, um, to, to fight its way to find its way into the institution is as viable, uh, techniques. Right. Um, and, and it kind of, um, you know, the master narrative suggests that there is no technique. There is no form inside of west African dance inside of hip hop, just as, um, truth was talking about. Um, but there is no history. And so what we get to do is to be able to teach people and to get closer to that history. Um, and so to go back to that and be able to, um, just make visible, um, the very, um, the, you know, the knowledge that comes from, uh, from the continent and the diaspora as well.

Speaker 1:

That's, that's really interesting because actually, um, in others sessions of this podcast in the last season, we talked a lot about anti racist teaching, not being only against something, but for something. And what you just described, both of you is that anti racist teaching dance and African dance in particular is both working to disrupt dominant ideas about dance and the discipline of dance and facilitator returning to like one soul to one's body. And so I see this, the dance between what you're against and also what you're for, um, in what you both have shared. So as parks, the question of what does this look like when you teach this way in your classroom? And I wonder, um, maybe Shani, if you'd be willing to get us started, like, what does it look like if we were sitting in your class or in your classroom right now, what anti racist teaching through dance and manifesting as

Speaker 3:

Yes, it manifest as, um, this mutual ground, right? This mutual space that we don't see, we're talking about, like master narratives in and manifest them that I'm not all knowing, right? Like I'm not, you know, there there's a mutual ground here. There's a reciprocity between my students and I, right. There's this idea that we're all experts, right. In our own knowledge in our body brings so much knowledge to the space, no matter where you're from. Um, just even into culturally speaking. So it looks like for me, like a circle, um, you know, where there is a, it's a communal, um, aspect to the work, and there is a call and response that is directly related to, you know, um, African ways of being right. Um, that's right there in the oral history. And so, you know, for me, um, it, it also looks like me being able to facilitate, um, others abilities inside of their bodies.

Speaker 3:

It looks like there were valuing different aesthetics, right? And there were valuing different sensibilities, not focusing so much on our eyes or even our intellect, but allowing the aspects of our soul, um, allowing like even inside of the music, right. Hearing the drums and how intrinsic that can be allowing our bodies to really like open up and to be open to these other sensibilities and, and from me and truth. And I as well, um, being able to facilitate this experience, um, can be really transforming inside of west African dance for students and for us now. Um, and so, um, that's, that's what I was saying in terms of, um, us noticing other aspects and how it plays out a little bit and what we call the studio. Right?

Speaker 1:

Yeah. Truth. I know you teach a lot with, with shiny. You want to add to like what that looks like for you or from your perspective, um, how we manufacture.

Speaker 2:

Yeah. Um, absolutely. Um, actually Shawnee and I were having a conversation the other day about basically in higher education, we're always talking about how do we create more inclusive spaces? How do we help different populations feel more included? And when I was telling Shawnee, I feel like when you go to an African dance class, that's a master class and inclusion, and I'm going to break down exactly why you get there no matter who you are, everybody has to make a contribution. If you come in in a wheelchair, somebody is going to hand you a bill that you're going to be using. If you're a little baby, they're going to put you also drums. They got to give you a tambourine, right? You win. When we're having class, you see people across and I'm talking a little bit more about the community oriented African dance classes.

Speaker 2:

But I think a lot of the lessons can be translated into higher ed education. You see people who are, um, youth to elders. I mean like 75 year old women still taking dance class. Do you see women who are pregnant? Everybody who comes in the room is acknowledged for their personhood. And that's fundamental to the experience. And then also as Shani was saying, in terms of the bodily experience, um, African dance is done in harmony with the drummers. So once again, getting back to the African aesthetic, it's not like you just come to class and you do what you want to do. And you just feel so free because you hear the, like, the drummer holds all the rhythms and the drummer is telling you what to do next. So you're constantly, and then the drummer is literally reading your body the whole time to know.

Speaker 2:

And so you create this synergy between the dancers and the drummers, right? And that's another aspect of, of this interdisciplinary or this interdependence that happens in the experience that is of high value. Um, in terms of thinking about like, how do you create these collaborative experiences and that also Shawnee referred to the circle, which is a really important part of African Indian. So at the end we circle up and we come in and we all do our own expression, our own take on what you learned. And no one gets a free pass. Like you can't just be like, okay, I'm gonna stand back on the circle time. Like, it's serious. Like if you do not come into the circle, it's, you know, it's not really, it, that's what the experience is all about. So those are just some examples of how we can take some of those values from African dance, right? Those values that make people, um, feel seen valued, um, honored in their body type, um, and in their abilities. Because when you go to some of these community classes, there are people who've been dancing for years and people who've just started dancing, but there's a way that space is held for anyone who comes in. So to me, that is what, um, excites me, energizes me about African dance. And I try to bring that to higher ed whenever I have the opportunity to teach within the higher ed context.

Speaker 3:

I just wanted to also add with that, how that's so different. Um, and why it's so important is because as a dancer, as you're training, like for instance, I went to like a right as a dancer. And so sometimes we're trained the complete opposite. We're trained to be remote, right from the emotions to pull back to not fully express ourselves tonight, even lean into the space where you're being moved by music, um, or even seeing other people in the space just to see someone in the space and to be able to make eye contact and to feel that exchange of energy is sometimes discouraged and, and looked down upon in some parts of the field. Right. And so this is why this space is so, so important in terms of including all of ourselves right inside of

Speaker 4:

That's so beautiful. Uh, thank you. Thank you both for providing that perspective. And, and I, I can, I can really relate to what the, both of you are saying. Um, despite not being a dancer myself, like by, by, by practice. Um, I do have a musical background and specifically I've, I was a drummer. Um, and, and, you know, thinking back to just my experience in music, it very much is this like collective experience. And it's a very visceral, very emotional experience to the point where like, I'm not going to lie sometimes when we would perform, I would be crying during the performance because it just got to my core. And it's, it's almost like this, um, w which one of you referenced this, that it's like making, making knowledge visible in some form, you know, you feel it, you express it, you convey it in some way.

Speaker 4:

And in both of you, what I pick up on the, both of you alluded to is like, there's a lot of intentionality about what's taught that the process is also like very, very focused. And then, you know, just really focusing on that communal experience, um, something, um, in, in Shawnee, uh, what, what you shared, um, is a perfect segue to our next question. Actually, something that fascinates me is just as human beings, how we're in this constant state of evolution, you know, every day we're S we're changing on a second to second basis on a cellular level we're changing. And so I'm really curious to know how the, both of you have evolved over time and, uh, Shawnee, you know, this is the first time that we meet, but I I've, I've read a little bit about your work, and it's really quite fascinating how your experience in the American dance festival, you know, really exposed you to, uh, just your professional growth, uh, you know, meeting and studying with, with, uh, some very influential teachers in different spaces as well. You visited MIT, you were at duke as well. And then in truth, I mean, you're, you're, you you've been nationwide worldwide, you know, you've been in different spaces. And so I'm just curious to know how have the, both of you come to teach and express and share the way that you do. And I'd like, uh, truth. Could you kick us off with that question, please? Thank you for that question.

Speaker 2:

The bottom line is that African dance changed my life. I was six years old when I took my first African dance class in an afterschool program. And the way that I felt in my body, the freedom that I felt at six years old left, quite the impression on me. So later middle school, high school years, I was really into like modern and more ballet and jazz. And I was really interested in, like, I wanted to be an Alvin Ailey dancer. That was like my idea of like, what it meant to be a dancer, um, which they do draw from, um, African dance forms. But, um, you have to have a very strong foundation in modern jazz and ballet. Um, obviously that did not happen in my life, but it just shows that there was a point where I did study ballet modern and jazz, but it was something about when I got to college, I got reintroduced to African dance and it just clicked for me in that moment.

Speaker 2:

And from there, that's where I felt like that was home for me as a dancer. Um, the doors that have opened for me have, have been limitless in the sense that I have been able to perform, um, at the time, um, with my African dance teacher and her dance company. And, um, then I had gone on to teach several years later and, um, and Shawnee and I were able to take our students to Senegal. And while we were there, we perform, um, at Ecolab disarm blaze, which is a really famous dance school there. So it has opened multiple doors for me, but I, I want to say the main thing that African dance has done for me is created that, um, that intervention in terms of helping me, um, to speak back to that master narrative that we were talking about in the beginning of this conversation, it gave me a space to, um, develop myself in my fullness and to appreciate my history and my culture from the African continent. And what does that mean as an African diet eSport person and how do I make meaning of all of that? And it created a space, not just an intellectual space, but an embodied space for me to discover who I am and to feel affirmed in that environment.

Speaker 3:

And, um, thank you truth. This is interesting to reflect on, um, how, you know, the journey, um, that, that Scott and me here. And, um, I was thinking about as you were talking truth about the Alvin Ailey school of bands, uh, one summer I, um, I did the eight week program in New York city when I was a young, young dancer. And actually at that time, I'm going to tell you, I was scared of west African dance because the circles that that truth is talking about, where is this? It's, it's an expectation that everybody participates. It frightened me. Like I was really nervous to have to go into the circle to dance, like, you know, to the point where I might rely story out to the bathroom, or like try to get away. You know, I knew it was coming up. It was like a big thing.

Speaker 3:

Um, but that, when I looked back at it, that has really contributed to just my transformation as an artist, me learning how to create my own language, um, in my body, me being free, you know, to be able to move in front of people and for them to be able to witness that. But in terms of like, um, you know, how I came to teach this way, I had a lot of models. Um, that one in particular, there was a, um, a man who taught west African dance at the Ailey school that summer who brought in, um, dreams this poem by Langston Hughes. And it was so interesting because here we are in a dance class and we recite this poem dreams at the end of every dance class, hold fast to dreams, you know, uh, for a dreams go, is this whole point. And so, um, I think in terms of looking at, um, you know, different elders and the mentors that I've had and how they use the space of the studio has really influenced how I, how I teach.

Speaker 3:

Um, in that particular instance, you know, he's talking about everyday things, you know, he's talking about dreaming, he's talking about how we're treating people. Um, you know, that, that everybody, like I said before is on a mutual ground. And so right away, uh, dance became a reflection of, of, of life and, and I could express life and what I was experiencing, you know, in the dance. And I began to see that particularly in the west African dance class, despite of my fear, um, you know, around, around the circle in particular. But I think also it's in the thinking of it because, um, having these spaces, um, where I felt affirm, I talked before about training in ballet, um, as a young dancer, having to like, you know, practice and getting rejected because my body and the way that my body looked like I had big size, I had a swayed back and I remember practicing a lot to try to get the sweat out of my back.

Speaker 3:

Um, and so that dichotomy of me trying to fit in, and then me feeling like home in these other spaces where I'm talking about really spoke volumes to me in terms of, um, the spaces that I created students or even bodies to come into and how important it is for people to feel like you see them, um, for my students to feel like they're heard, um, for them to feel like they belong. Right. And so that was just really influential to me as well as kind of being born out of this, uh, black arts movement out of the black liberation movement, which is really defining, you know, whiteness in ways and really being radical about, um, creating our own spaces, uh, for, for liberation.

Speaker 4:

Thank you. Thank you both for your answers. Um, I I'd like to expand and, and uplift a note that you mentioned Shani that's, uh, that's that the, both of you in this process create a new language. And I love that. Um, and in, in a way I imagine that it helps students speak perhaps in a way that they didn't think that they could before or express themselves in a way that they knew that they couldn't before. And it's, it's made me think that knowledge, and I'm even beginning to like, deconstruct these ideas, these Western, you know, Eurocentric constructs about how knowledge is viewed in just one way, if it's not written, it's not valid, um, and how knowledge creation and expression is. So multi-dimensional, um, I think in, in my experience with music, I think it's, it's uplifted me in moments where I've been at my worst, and it's also enhanced my life in times when it's just, it's been full of happiness, you know, and it's there there's no one size fits all approach, you know, it's just, it's so multi-dimensional, and so I'm just curious to know from, from the students that you both teach, what's their experience and how do they respond to the approaches and the process and the experiences that you both convey and share, um, Shani would, uh, would you like to kick us off with that question?

Speaker 3: