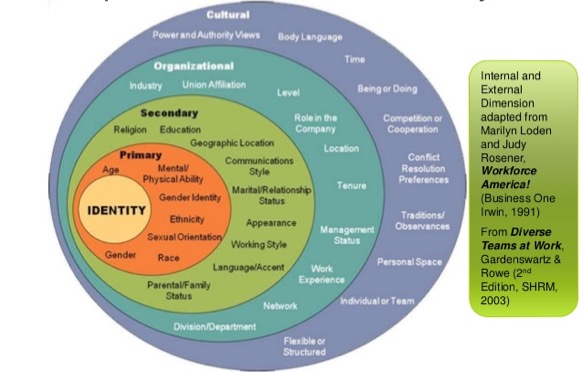

Both students and instructors bring their educational backgrounds, lived experiences, cultures, and identities with them into any learning situations. It might seem impossible to get to know every student you teach, but it is vital for instructors to reflect upon differences between their own experiences and that of their students.This diagram, borrowed from a business context, illustrates layers of identities and may be helpful in reflecting on diversity and intersectionality in the classroom.

CETL has curated a set of resources to help instructors reflect on the role of identities in the classroom, as well as tools and resources for practice. You may also wish to consult resources on equity-minded teaching practices.

Who are UConn students?

It is valuable to have a sense of what life is like once students arrive at UConn. The following demographic and institutional information is intended to provide an overview to support reflection about the students you may be teaching.

In 2020, there were more than 24,000 undergraduate students enrolled at the University and more than 8,000 Graduate/Professional students. Among undergraduates, eight percent are international students, while 21 percent of graduate students are international. There are 110 countries represented in the UConn student body. All 169 Connecticut towns and 39 of 50 U.S. states are represented in the undergraduate population.

Among undergraduates, the average time to graduation is 4.2 years. Tuition is $31,092 for in-state and $53,760 for out-of-state. In 2020, 8,776 bachelor’s degrees were awarded. The majority of students are enrolled at the Storrs campus, but UConn has other campuses with regional identities of their own: Avery Point, Hartford, Stamford, Waterbury, as well as a Law School campus and the UConn Health Center in Farmington.

More than 50 percent of entering first year students are in the top 10 percent of their class. In any given classroom there is likely to be a transfer student; across campuses there are more than 1,200 transfer students. More than 10,000 UConn students commute or live off-campus. Many are first-generation students.

Most recent demographic data show that about 12,000 UConn undergraduates identify as White. In fall 2020 there were 3,791 Hispanic/Latino students, 2,842 Asian students, 1,916 Black or African American students, 22 American Indian or Alaska Native students, nine Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander students, and 914 students who identified with two or more races.

At the Storrs campus, there are more than 100 residence halls, ranging from traditional dormitories, apartments, and suites to special interest residences, learning community halls, and fraternity/sorority housing. The campus spans 4,000 acres.

For more information about graduate students, please visit the Graduate School.

What do UConn students study?

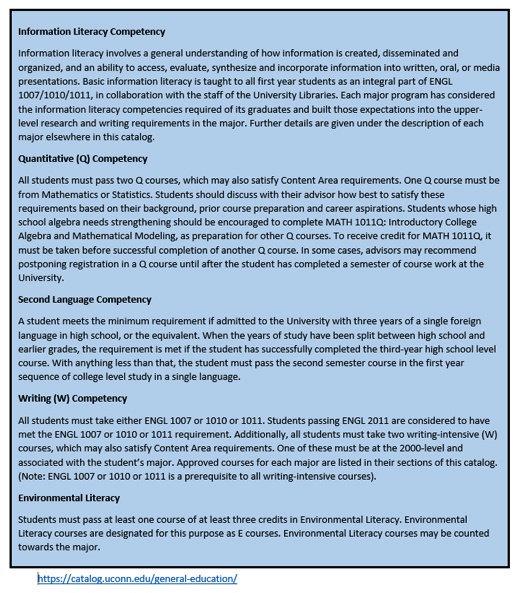

In addition to selecting a major, undergraduate students fulfill general education requirements to “become articulate and acquire intellectual breadth and versatility, critical judgment, moral sensitivity, awareness of their era and society, consciousness of the diversity of human culture and experience, and a working understanding of the processes by which they can continue to acquire and use knowledge” (University Senate)

At UConn there are more than 115 majors. Majors with the most students (Storrs campus) were biology, economics, psychology, mechanical engineering, and finance.

Through its general education requirements, the University Senate aims to “ensure that all University of Connecticut undergraduate students become articulate and acquire intellectual breadth and versatility, critical judgment, moral sensitivity, awareness of their era and society, consciousness of the diversity of human culture and experience, and a working understanding of the processes by which they can continue to acquire and use knowledge.”

Students are required to complete at least 6 credits (typically two courses) in each of the following areas:

Content Area One Arts and Humanities

Content Area Two Social Sciences

Content Area Three Science and Technology

Content Area Four Diversity and Multiculturalism

In addition, UConn undergraduates need to demonstrate competency in four fundamental areas: information literacy, quantitative skills, second language proficiency and writing. There is also an environmental literacy requirement.

Identities in the classroom

In a student-centered paradigm, where we teach the student rather than teaching the material, it is fundamental to become aware of, value, and activate diversity in order to provide students with an environment that is conducive to their learning.

Faculty have a number of roles inside and out of the classroom. They are content experts, facilitators, curriculum designers, advisers, graders, and mentors. In this demanding work, it can be challenging to stay student-centered. Here is a short list of practices for a student-centered teaching toolkit that is responsive to the situated, contextual nature of learning:

- Recognize your own implicit biases and build cultural literacies and competencies

- Do not expect a student to speak on behalf of everyone with a similar background;

- Design your course to be more representative of diverse cultures and people

- Take the time to learn about your students' background, interests, and preferred learning modalities to create an environment conducive to each student;

- Provide time for the students to learn about each other, gain an appreciation for the diversity they bring to the classroom, and take advantage of each other’s strengths to produce the best possible results;

- Share your stories

- Address diversity tensions when they arise; and

- Communicate ground rules regarding speech and behavior frequently, including any zero tolerance policies and their justification.

CETL has curated a set of resources to help instructors reflect on the role of identities in the classroom, as well as tools and resources for practice. You may also wish to consult resources on equity-minded teaching practices.

Spotlight on overall generational differences in the classroom

The COVID 19 pandemic changed the way students engage in coursework and in classes. Even without the pandemic it has been a longstanding practice to reflect on contexts for learning that change with each passing year--otherwise known as “generational differences.”

The COVID 19 pandemic changed the way students engage in coursework and in classes. With more asynchronous course designs, more pass/fail options, and synchronous or hybrid modalities requiring technology to access and participate, students who attended high school or college from March 2020 onward experienced an abrupt need to adapt to almost entirely online learning. The pandemic had variable effects on students, in many cases exposing stark inequities in educational systems. In the case of many college students who found themselves at home or in other ways unexpectedly away from their social circles on campus, the experience of learning during the pandemic was substantially less social. There seems to be consensus that the changes to education will reverberate in an ongoing way that carry risk for more vulnerable students but also the possibility of sustained innovation in teaching methods.

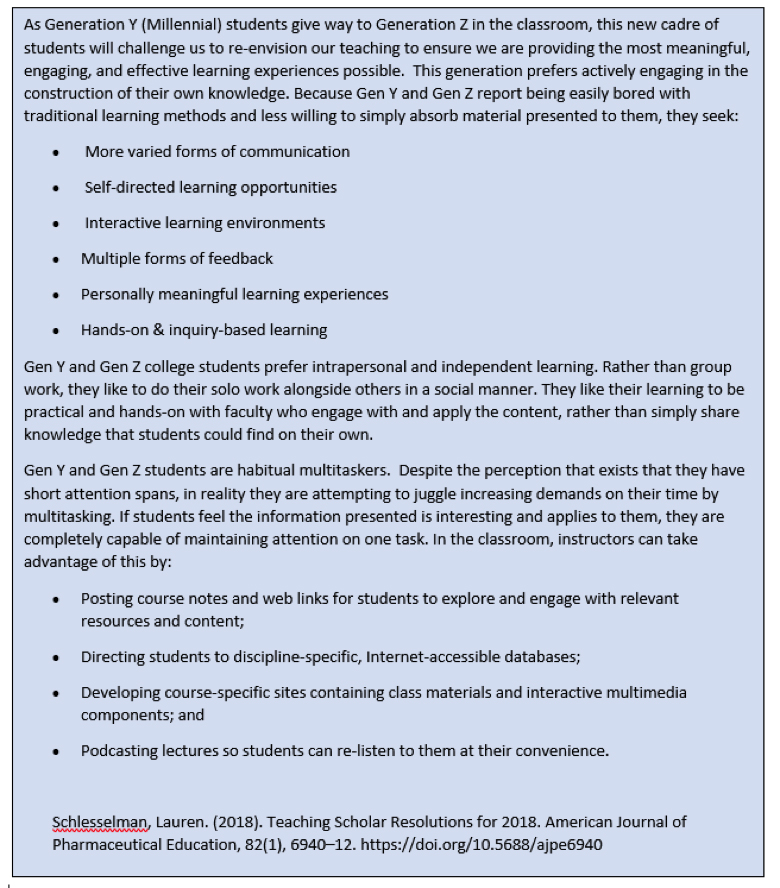

Even without the pandemic it has been a longstanding practice to reflect on contexts for learning that change with each passing year--otherwise known as “generational differences.” Lauren Schlesselman summarizes research on generational differences this way:

Despite overall generational differences in how a student might learn most comfortably, it is worth reminding ourselves that people of every age tend to share more similarities than differences. The transition from one chronological generational cohort to the next is unlikely a sharp cutoff. We also cannot make assumptions about any one individual based on age. Good teachers tend to worry less about theoretical generational differences and begin by identifying the needs of any given set of learners in their context. Still, instructors may gain some confidence from learning about popular culture references that students will find meaningful, and should certainly refresh their own curiosity about events and circumstances that have shaped students’ lived experiences.

Resources

Quick Links

![]()

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.