Take a moment to think back to your time as a student and recall some of your favorite courses. Very likely, those courses were well organized, assignments were clear, lectures and classroom discussions were focused and interesting, and the professor conveyed a passion for teaching and compassion for the students. How can you create such an environment in your own courses?

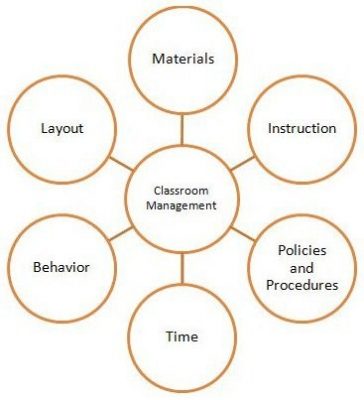

Effective classroom management entails meticulous planning but also a readiness to switch gears and move away from the script when necessary; it requires firm control but also a willingness to relinquish that control to take advantage of a teachable moment; it requires leadership but also a sense of compassion and understanding of your students.

Behavior Management ≠ Classroom Management, Education Week

Effective classroom management begins with strong organizational skills—preparing your materials carefully, practicing with the technology, and getting a sense of how to best organize and move around in the room, but that’s not where the planning ends. Consider these techniques as you develop your classroom management style:

Begin to establish an effective environment on the first day of class

First impressions are extremely important in setting the tone for the rest of the semester, so plan your first class carefully:

- Introduce yourself. Explicitly state the way you would like to be addressed.

- Consider offering an ice breaker to relax students and encourage interaction.

- Teach something; immediately begin to engage students in the course.

- Take class time to review the syllabus and emphasize important aspects. In fact, use the syllabus to begin building student engagement even before you meet with students by ensuring that it articulates learning outcomes, class format, and expected behavior. During those first few hectic add/drop weeks, students appreciate an instructor who clearly and concisely presents a course overview.

- Expect some students to come in late. They’re getting lost, too!

- Consider setting community rules (e.g., regarding phones, laptops, talking, sleeping, eating, late arrivals, and early departures) with the students; they will appreciate the democratic approach.

- Start learning names right away; anonymity discourages student engagement. Using props (name cards, photos, index cards), taking attendance (but remember that UConn policy prohibits grading attendance), and handing back papers and homework can help you to connect a name with a face.

Refer to First Day of Class for more information on first class activities and learning students’ names.

Interact with students regularly

Consistent interaction will help ensure rapport and reduce classroom management issues:

- Greet students as they enter the classroom

- Chat with them for a few moments—Consider opening class with a brief casual conversation about a current event or something interesting from the homework

- Intersperse lecture with discussion, group work, or video segments to encourage involvement and help students connect the content with real-world events and issues

- Ask questions (giving plenty of wait time) and respond to student comments

- Make eye contact with as many students as possible during class

Be ready to respond to challenges

The best way to avoid challenges in the classroom is to anticipate the possibilities ahead of time and plan accordingly.

What will you do if students consistently arrive unprepared?

Students spend only about half the time preparing for class as faculty expect. When faculty expect students to study more and arrange class to this end, students are more productive (National Survey of Student Engagement, 2004).

How will you handle disruptive students?

Frequently we hear instructors lament the poor behavior of students in the classroom. UConn instructors are not the only ones who are noticing declining classroom courtesy (Schneider, 1998). This decline in courtesy and civility is resulting in frustration for instructors and students alike, reduction in student learning and student retention (Seidman, 2005).

Feldman (2001) characterized four general types of classroom incivility:

- Annoyances;

- Classroom terrorism;

- Intimidation of the instructor; and

- Threats or attacks on a person or person’s psyche.

These four types of incivility range from arriving to class late (annoyances), to monopolizing classroom time with personal agendas (labeled as classroom terrorism by Feldman), to threatening to go to the department chair with complaints or give negative course evaluations (intimidation), to threats of physical violence or even physical attacks. The impact of each of these types of incivility on learning varies greatly but all of these types of incivility can disrupt the learning process.

Be proactive. When it comes to promoting classroom civility, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Expectations for behavior should be included in your syllabus, presented on the first day of class, and revisited as necessary. Along with elaborating on your expectations, the consequences for violating these expectations should be specific and consistently explained and enforced. UConn’s standards should also be included so all students are aware of university policies and what is expected from them as citizens of the university community.

Be specific. Contrary to what you may think and hope some college students have not learned how to behave appropriately in the classroom. Therefore, it is necessary to provide very specific expectations. Rather than telling students to “be respectful,” provide them with examples. Can students disagree with the opinions of others? Can they ask questions while you are lecturing? Can they record your lecture? Alternatively, must they express their dissenting viewpoint or ask questions in accordance to certain expectations? If so, explain what those expectations are expectations.

Be in control. By studying university policies and thinking through possible problems you can develop a plan of action. Although you cannot anticipate all occurrences, you can develop plans that will help in many different instances. Whether the incivility was something you addressed in your syllabus or some type of unexpected incivility, typically, immediate action is necessary to demonstrate that you have control of the classroom. The specific action taken will depend upon the infraction. UConn provides information on student conduct on the website for Community Standards. Incivility should be carefully documented along with how you handled the situation and the student’s response.

Be a model. Your own behavior serves as a powerful representation of how you want students to behavior in the classroom and treat you and their classmates. You cannot demand respectful behavior from students if you are not respectful of them.

How can you encourage students to become engaged? It can be difficult to determine why quiet students are not contributing: Are they shy or introverted by nature, do they suffer from anxiety or depression, or are they simply unprepared? Here are a few ways to tease out discussion:

- Give weekly quizzes, reflection papers or homework: Many students come from a test-laden, grade-driven public school experience, so they may not think that ungraded assignments are important. Connecting preparation to even a minimally graded assignment may dramatically increase students’ motivation to do their homework.

- Clarify concepts and help with problem solving: If you work with material in class, acknowledging students’ ideas and offering valuable feedback, students will come to expect that they need to be prepared.

- Grade class participation: Ask your students to help establish participation expectations in the class, and then grade their contributions to discussion using a rubric, clickers, or other methods.

- Flip the classroom: Instead of using class time to lecture on the reading, establish an expectation that students must read or watch an online lecture before class in order to complete a classroom exercise (which may include group work, a case study, problem-solving, etc.).

- Make expectations clear: Set ground rules for discussion, set criteria and indicators for participation, and model those behaviors. If students appear unaccustomed to discussion, provide scaffolding by assigning roles or specific techniques (Brookfield, 2011).

- Call on students by name: When students sense that they are anonymous, they may not feel compelled to speak; show them that you are aware of them and interested and respectful enough to learn their names.

- Respond positively and encourage elaboration: Learn to reply to student comments in a way that encourages participation. For example, students are more likely to participate when they do not feel threatened in class, so instead of saying, “No, that’s wrong,” you might ask a question that leads students to discover the error on their own. Acknowledge comments by repeating or rephrasing parts and commenting on them directly.

- Introduce active learning exercises: Students who feel too on-the-spot to contribute to whole-class discussion might flourish in small groups, role plays, etc. When possible, offer a variety of ways for students to participate.

- Give think time before expecting students to respond to questions: Some of our best thinkers simply need a little time to collect and articulate their thoughts. Give 10, 15 or even 30 seconds for students to answer tough questions, all the while making eye contact with them (showing that you will wait for an answer). Or ask them to take a few minutes to jot down notes and then ask what they came up with. You can also try think-pair-share exercises: After thinking and jotting notes, students discuss their responses with a nearby peer before sharing with the class.

- Show your enthusiasm: Students will participate more often if their instructors engage actively in the discussion and show that they genuinely value participation.

The first step to getting students engaged is to get them to actually show up for class. Please see our tips on improving student attendance.

Should you post your lectures, slides, in-class materials, etc., online? Weigh the pros and cons, decide on a strategy and then stick with it: Posting class materials can save time, give students more opportunities to interact with the material, and make information accessible to everyone. On the other hand, posting may reduce attendance and class interaction, and it appears to encourage a passive approach to learning.

Tips: Remember…Engage, engage, engage!

Don’t let down once the course gets underway.

- Arouse students’ curiosity

- Convey your passion for the subject

- Make course material relevant

- Assign challenging but achievable tasks

- Give students some control over their learning

- Be available to meet students before and after class and during office hours

Articles referenced above:

Feldman, L. (2001). Classroom civility is another of our instructor responsibilities. College Teaching, 49(4), 137-141.

Schneider, A. (1998). Insubordination and intimidation signal the end of decorum in many classrooms. The Chronicle of Higher Education, (March 27), A12-A14.

Seidman, A. (2005). The learning killer: Disruptive student behavior in the classroom. Reading Improvement, 42, 40-46. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/ docview/62148142?accountid=27975

Resources:

Berger, B.A. “Incivility.” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education 64 (4), 2000. Available at: http://archive.ajpe.org/legacy/pdfs/aj640418.pdf

Carbone, E. "Students behaving badly in large classes." New Directions for Teaching and Learning 77, 1999. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tl.7704/abstract

Flaherty, C. “How not to lose control of a class.” Inside HigherEd; May 2015. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/05/26/seasoned-educators-weigh-not-losing-control-class

Galbraith M.W. and Jones, M.S. “Understanding incivility in online teaching.” Journal of Adult Education 39(2); 2010. Available at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ930240.pdf

Knepp, K.A. “Understanding student and faculty incivility in higher education.” Journal of Effective Teaching 12, 2012. Available at: http://www.uncw.edu/jet/articles/Vol12_1/Knepp.pdf

McKinney, M. “Coping with ‘Oy Vey’ students.” Inside HigherEd 2005. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2005/12/19/coping-oy-vey-students

Stewart, M.S. “Cropping out incivility.” Inside HigherEd 2011. Available at: https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/a_kinder_campus/stewart_on_creating_a_more_civil_campus_environment

Tiberius, R., and Flak, E. "Incivility in dyadic teaching and learning." New Directions for Teaching and Learning 77, 1999. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tl.7701/abstract

Additional resources:

Bain, Ken (2004). What the Best College Teachers Do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McGlynn, A.P. (2001). Successful beginnings for college teaching: Engaging your students from the first day of class. Madison, WI: Atwood Publishing.

McKeachie, W. J. and Svinicki, M. (2013) McKeachie's teaching tips : Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Silberman, M.L. (1996). Active learning. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

20-Minute Mentor Tips

Thanks to our institution subscription to 20-Minute Mentor you have countless teaching tip videos available at the click of a button. Here is one related to this topic:

How do master teachers create a positive classroom?

If you have not signed up for your subaccount, here is how: http://cetl.uconn.edu/20-minute-mentor-commons-subscription/

Quick Links

![]()

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.